To view the message as a file click here

Abstract

This document presents the macroeconomic staff forecast formulated by the Bank of Israel Research Department in January 2024[1] concerning the main macroeconomic variables—GDP, inflation, and the interest rate. This forecast was formulated in the midst of the “Swords of Iron” War, which broke out on October 7, 2023 with the cruel attack by terrorist organizations from Gaza. This forecast is an update of the forecast that was published in November outside the normally scheduled quarterly forecasts. Similar to the November forecast, this forecast was built under the assumption that the war’s direct impact on the economy will have reached its peak in the fourth quarter of 2023, and that it will continue until the end of 2024 with decreasing intensity. For 2025, the forecast assumes that the war will have no additional significant impact. In addition, we assume that for the most part, the war will continue to be restricted to Gaza. The forecast naturally features a particularly high level of uncertainty, partly with regard to the duration and nature of the war in Gaza and the potential worsening of the situation on the northern front, and with regard to decisions that the government will make regarding how the budget will deal with the defense and civilian needs arising from the war.

According to the forecast, GDP is expected to grow by 2 percent in 2023 and in 2024 (similar to the November forecast) and by 5 percent in 2025. The inflation rate in 2024 is expected to be 2.4 percent, and in 2025 it is expected to be 2 percent. The interest rate in the fourth quarter of 2024 is expected to be 3.75/4.00 percent.

The forecast

The Bank of Israel Research Department compiles a staff forecast of macroeconomic developments based on several models, various data sources, and assessments based on economists’ judgment. The Bank’s DSGE (Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium) model—a structural model developed in the Research Department and based on microeconomic foundations—plays a prime role in formulating the macroeconomic forecast.[2] The model provides a framework for analyzing the forces that have an effect on the economy, and allows information from various sources to be combined into a macroeconomic forecast of real and nominal variables, with an internally consistent “economic story”.

In order to formulate estimates of the economic impact of the war, special emphasis was placed on an analysis of real-time data that show the scope of the impact so far on the output of various industries and on uses, as well as on an analysis of past security incidents. In addition to the use of the DSGE model, we used industry-level assessments of the volume of the supply-side impact derived partly from the lack of workers during the war period and the security restrictions on activity. On the demand side, data obtained so far were analyzed in order to assess the impact on the various uses. The results were integrated into a full forecast of the sources and uses using an analysis of the relative severity of the demand and supply restrictions in the various activity components.

- The global environment

Our assessments of expected developments in the global economy are based mainly on projections by international financial institutions and foreign investment houses. The main assumptions regarding the global environment remained similar to those used in the November forecast. Accordingly, we assume, similar to the November forecast, that growth in the advanced economies was 1.3 percent in 2023, and that it will be 0.8 percent in 2024, and 1.5 percent in 2025. Our assumption is that world trade grew by 1.2 percent in 2023, and that it will grow by 3.5 percent in 2024, and by 3 percent in 2025. The inflation forecasts for the advanced economies were revised. Accordingly, our assessment is that inflation in those countries will total 3.1 percent in 2023 (compared with 3.4 percent in the November forecast) and 2.3 percent in 2024 (unchanged from the November forecast). Our assumption is that the 2025 figure will be 2.2 percent. Investment houses’ forecasts of the average interest rate in the advanced economies are 3.9 percent at the end of 2024 (unchanged from the November forecast) and 3.1 percent at the end of 2025. Despite some volatility in recent weeks, the price of Brent crude oil remained similar to its level at the time of the November forecast, around $80 per barrel.

- Real activity in Israel

GDP is expected to grow by 2 percent in each of 2023 and 2024 and by 5 percent in 2025 (Table 1).

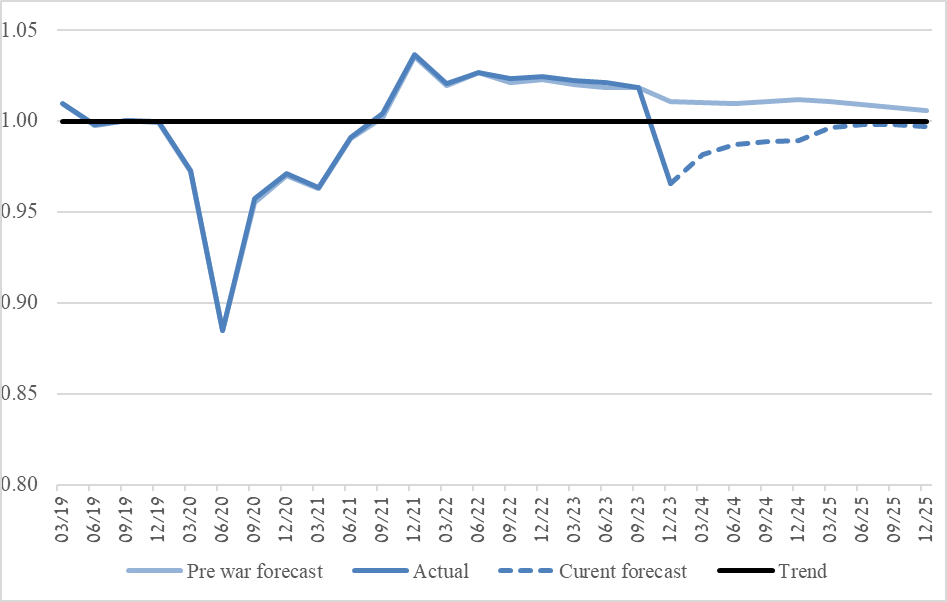

The forecast in Table 1 is based on the assumption that the war’s direct impact on the economy reached its peak in the fourth quarter of 2023, and that it will continue into 2024 with declining intensity. In 2025, a recovery is expected, which will support the GDP’s convergence to the trend that it showed between 2014 and 2019, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 1). The expected effect on GDP in 2023 and 2024 is due to the negative impacts on both the supply side and the demand side. On the supply side, the broad emergency mobilization of the reserves and the partial shut-down of educational institutions, mainly in the first two months of the war, were reflected in a decline in the supply of labor in all industries. In the construction and agriculture industries, there is a very significant impact to the supply of labor—in construction due to restrictions on the entry of laborers from Judea and Samaria and the complete stoppage of employment of laborers from Gaza, and in agriculture due to the departure of foreign workers. In the present forecast, we assume that addressing these supply issues will take longer than previously expected. In addition to the decline in the supply of labor, production capacity in the combat areas and in threatened regions has been impaired due to the impact to physical capital and the ability to work.

On the demand side, our assessment is that negative consumer sentiment is expected to continue to have an impact on consumer demand. Demand for the export of tourism services (incoming tourism) has suffered, and experience from previous security incidents shows that this impact is expected to be prolonged. In contrast, in the construction industry, an increase in demand is expected within the forecast period, partly due to the need to rehabilitate structures. In view of these developments, our assessment is that the broad unemployment rate[3] among the prime working ages, which increased in the fourth quarter of 2023, will decline gradually in 2024, and will converge to its prewar level only in 2025.

Credit card purchases show that the level of private consumption is higher than we assumed in the previous forecast from November. In addition, foreign trade data indicate a sharp decline in imports alongside a more moderate decline in exports. These developments are positively contributing to both the growth estimate for 2023 and to expected growth for 2024. In contrast, in view of the restrictions on the entry of Palestinian laborers, which we assume will continue in the coming quarters, the construction industry will continue to show a significant decline in the volume of activity in 2024. This development leads to a downward revision of the forecast growth of investment and GDP in 2024. In the final analysis, the changes in the effects of the various accounting components on demand for output are expected to cancel each other out, such that there is no change in the growth forecast for 2023 or 2024—2 percent in each year, similar to the November forecast.

|

Table 1 Research Department Staff Forecast for 2023–2025 (rates of change, percenta, unless stated otherwise) |

||||||

|

|

2022 Actual |

Estimate for 2023 |

Change from the November forecast |

Forecast for 2024 |

Change from the November forecast |

Forecast for 2025 |

|

GDP |

6.5 |

2.0 |

- |

2.0 |

- |

5.0 |

|

Private consumption |

7.7 |

-0.5 |

- |

3.0 |

1.0 |

6.0 |

|

Fixed capital formation (excl. ships and aircraft) |

11.0 |

0.5 |

-1.5 |

-3.0 |

-4.0 |

6.5 |

|

Public consumption (excl. defense imports) |

1.4 |

9.5 |

1.0 |

6.5 |

5.0 |

0.5 |

|

Exports (excl. diamonds and startups) |

9.6 |

.0 |

-1.0 |

0.5 |

-1.0 |

5.0 |

|

Civilian imports (excl. diamonds, ships, and aircraft) |

12.7 |

-5.5 |

-2.5 |

-4.0 |

-5.0 |

9.5 |

|

GDP diversion from the pre-COVID trend, average during the year (percent) |

2.4 |

0.7 |

|

-1.3 |

|

-0.3 |

|

Broad unemployment rate (average for the year, ages 25–64)b |

3.6 |

4.5 |

0.2 |

5.3 |

0.8 |

3.2 |

|

Adjusted employment rate (average for the year, ages 25–64)b |

78.3 |

77.7 |

-0.4 |

76.7 |

-0.9 |

78.7 |

|

Government deficit (percent of GDP) |

-0.6 |

4.0 |

0.3 |

5.7 |

0.7 |

3.8 |

|

Debt to GDP ratio (percent) |

60.5 |

62.0 |

-1.0 |

66.0 |

- |

66.0 |

|

Inflation (percent)c |

5.1 |

3.3 |

-0.2 |

2.4 |

- |

2.0 |

|

a In the forecast of National Accounts components, the rate of change is rounded to the nearest half percentage point. b According to the Central Bureau of Statistics definition, the broad unemployment rate includes the unemployed under the normal definition (someone who has not worked, wanted to work, was available to work, and searched for work), as well as employees who were temporarily absent from their jobs for economic reasons (including furloughed workers). Accordingly, the adjusted employment rate does not include those temporarily absent from their jobs for economic reasons. c The average of the Consumer Price Index in the last quarter of the year compared with the average in the last quarter of the previous year. |

||||||

Figure 1 |

|

GDP relative to the pre-COVID trend – Forecast and actual (1 = Pre crisis trend, fixed prices, seasonally adjusted)

|

- The State Budget and fiscal policy

The forecast is based on the assumption that the government will make budgetary adjustments of around NIS 30 billion in order to offset the permanent increase in defense expenditures and civilian expenditures related to the war and its consequences. Accordingly, the debt-to-GDP ratio is expected to increase to 66 percent by the end of 2024, and to begin declining gradually in 2026 (Table 1).

Our assessment is that the impact to economic activity has led to a sharp drop in tax revenue in the fourth quarter of 2023, and that this will continue throughout 2024, declining gradually with the recovery of activity. We assume that defense expenditures will decline in line with the decreasing intensity of the fighting, but the defense budget will be increased in 2024 and 2025 beyond the cost of the war, in order to support a permanent strengthening of the military in terms of manpower and military purchasing beyond prewar levels.[4] In addition to defense expenditures, we assume that civilian expenditures connected to the war will total about NIS 10 billion in 2024 and about NIS 5 billion in 2025.

In our assessment, even after the completion of the programs directly related to the war, expenditures on defense, rehabilitation of damaged areas, and interest payments will be significantly higher than what would have been expected had it not been for the war. Our working assumption is that these costs will total about NIS 30 billion per year from 2025. In contrast, we assume that during 2024, the government will decide on budgetary adjustments that will include a reduction of other expenses or an increase in taxes, against the full permanent increase in expenditures. We assume that half of these adjustments will take effect in 2024, with the rest taking effect in 2025. As such, the increase in the budget deficit will be due to temporary expenditures only. The assumed need for the budgetary adjustments is due to the fact that, as opposed to the process to end government assistance programs that were utilized during the COVID-19 crisis, which ended once the pandemic was over, the current war will apparently be accompanied by a permanent increase in government expenditures. Therefore, the adjustments required to maintain the structural deficit at its original level are very important in order to show a government commitment to maintain fiscal responsibility by bringing about a downward path in the debt-to-GDP ratio in the years after the war.

The overall effect of all these is expected to be reflected in an increase in the government’s budget deficit to about 4.0 percent of GDP in 2023, 5.7 percent of GDP in 2024, and 3.8 percent of GDP in 2025 (Table 1). In view of this, the public debt is expected to increase to about 62 percent of GDP at the end of 2023, and about 66 percent of GDP at the end of each of 2024 and 2025. In the following years, the debt to GDP ratio is expected to decline moderately. In this scenario, the debt to GDP ratio is expected to reach about 63 percent in 2030, compared with 57 percent that was expected prior to the war. In contrast with the COVID-19 crisis, at the end of which the growth rates were unprecedented—in view of the sharp decline in activity at the beginning of the crisis, the rapid recovery of all advanced economies and the low interest rates that were common in 2021–22—the forecast for the years following the war is that growth will be in line with the pre-COVID trend, and even lower than it (insofar as the war, its results, and the policy measures that will be taken will have prolonged effects on the economy).

- Inflation and interest rates

According to our assessment, inflation in 2024 is expected to be 2.4 percent (Table 2), unchanged from the November forecast. The moderation of inflation within the forecast range, compared to 2023, reflects a trend that began even before the war, influenced by developments abroad and domestic monetary policy, as well as the recent appreciation of the shekel. It is also affected by the war’s impact on consumer sentiment and on private consumption. The forces moderating inflation are expected to be partly offset, mainly in the short term, by supply side interruptions due to the war, which should be reflected in an increase in the prices of goods and services. These constraints include an impact to the supply of labor in view of the mobilization of reserve forces, and an impact to production capacity and supply chain disruptions. With that, similar to previous forecasts, we assume that the effect of reduced demand is stronger, such that in the final analysis, the war will have a restraining effect on inflation. While the inflation forecast remains unchanged from November, it is affected by developments in opposing directions: The appreciation of the shekel and the lower-than-expected inflation in the November CPI are contrasted with the increase in the consumption forecast for 2024 (Table 1).

The interest rate is expected to be 3.75/4.00 percent in the fourth quarter of 2024 (Table 2). The interest rate level during the forecast period will help stabilize the financial markets and support domestic demand.

Table 2 shows that the Research Department’s staff forecast regarding the interest rate is higher than market expectations, while the Research Department’s inflation forecast is slightly lower than the market’s expectations. The forecasters’ projections for both the interest rate and inflation are similar to the Research Department’s forecast.

Table 2 |

|||

|

Inflation forecast for the coming year and interest rate forecast for one year from now |

|||

|

(percent) |

|||

|

Bank of Israel Research Department |

Capital marketsa |

Private forecastersb |

|

|

Inflation ratec |

2.4 |

2.8 |

2.3 (1.9–2.6) |

|

(range of forecasts) |

|

|

|

|

Interest rated |

3.75/4.00 |

3.4 |

3.6 |

|

(range of forecasts) |

(3.00–4.00) |

||

|

a) Inflation expectations are seasonally adjusted (as of December 31, 2023). b) The average of forecasts published following the publication of the Consumer Price Index for November 2023. c) Research Department: the inflation rate during the four quarters ending in the fourth quarter of 2024. |

|||

|

d) Research Department: the average interest rate in the fourth quarter of 2024. Expectations derived from the capital market are based on the Telbor market (as of December 31, 2023). SOURCE: Bank of Israel. |

|||

- Main risks to the forecast

The forecast is based on the assumption that the main part of the war will be on one front against the terrorist organizations in Gaza, and that its effects will continue into 2024 with declining intensity. Various developments that may affect the duration and severity of the war will obviously have a material impact on economic developments. In particular, an expansion of the war to the northern front, which, according to assessment, is more complex than the southern front, is expected to have a more serious economic impact. Such an expansion will be accompanied by an additional impact to growth, and for some time will lead to interruptions in the ability to conduct routine economic activity. As a result, it may again undermine stability in the markets and lead to upward pressure on inflation. In view of this possibility, our assessment is that the balance of risks to the Research Department’s forecast tends to be downward. In making policy decisions—both monetary and fiscal—it is important to recognize that there is considerable likelihood of such a development during the forecast range.

In the fiscal realm, there are risks to the forecast due to the uncertainty with regard to the volume and financing of government expenditures. If the government decides to further increase expenditures and/or avoid reducing other expenditures, the deficit and debt are expected to grow further accordingly. In a scenario in which the government chooses not to make any budgetary adjustments during the coming years, while significantly increasing the structural deficit, the debt to GDP ratio is expected to continue increasing even beyond the forecast range.

Such a policy is expected to have negative implications for the economy. These may be reflected in increases in the country’s risk premium and in bond yields, a possible lowering of the country’s credit rating, a depreciation of the shekel, an increase in the interest rate, and an increase in inflation. In such a scenario, the burden of interest payments on the debt will increase even further in the coming years, in addition to the increase in defense and civilian expenditures. The increase in the interest rate, alongside the impact to market trust, are also expected to lead to investments being crowded out, which would lead to a decline in potential GDP and in growth in the following years.

It is difficult to predict the intensity of the response of Israel’s risk premium and its effects on economic activity. In order to examine the debt’s sensitivity to the growth rates and the interest rate on public debt, we analyzed different scenarios in which the government does not make any adjustments. In the first scenario, the markets respond in a linear fashion, the debt gradually becomes more expensive due to an increase in demand for capital on the part of the government[5], and GDP grows from 2026 onward according to the potential growth rate. In the other scenarios, the financial markets’ risk premium responds earlier to the expected growth of the debt to GDP ratio: The interest on new debt raised jumps by 100 basis points in 2024, and continues to increase in a linear fashion with the increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio. In some of these scenarios, the increased risk premium also contracts economic growth by 0.5 percentage points during each of 2024 and 2025, before climbing back to its pre-COVID and prewar levels, while in other scenarios the contraction of the growth rate becomes permanent. The results of the simulations show that the debt to GDP ratio is expected to increase rapidly under some scenarios, such that by the year 2030, it would reach to 72–80 percent of GDP, compared with 63 percent in the scenario that includes the adjustments required to fully offset the permanent increase in expenses. It is difficult to assess when exactly the markets will react to such a dynamic, but in the end, as experience in Israel and abroad shows, it will require adjustments on a much larger scale than what is necessary today.

[1] The forecast was presented to the Bank of Israel Monetary Committee on December 31, 2023, prior to the decision on the interest rate made on January 1, 2024.

[2] An explanation of the macroeconomic forecasts formulated by the bank of Israel Research Department, as well as a review of the models on which they are based, appear in the Bank of Israel’s Inflation Report 31 (second quarter of 2010), Section 3c. A Discussion Paper on the DSGE model is available on the Bank of Israel website, under the title: “MOISE: A DSGE Model for the Israeli Economy,” Discussion Paper No. 2012.06.

[3] In addition to the unemployed, the broad unemployment rate includes those temporarily absent from their jobs for economic reasons (including furloughed employees).

[4] We assume that the entire defense grant from the US will be received in 2024, even though it has not yet been approved. If this does not come to pass, it will require a greater increase in the defense budget (and in the deficit) and/or a deferral of security expenditures to future years.

[5] Bank of Israel studies have shown that an increase of one percent in the public debt to GDP ratio increases the real yield on long-term government bonds by 10 basis points.