![]() To view this press release as a Word document

To view this press release as a Word document

v The human capital of those employed in the information technology industries is unique, and that uniqueness has grown more pronounced since 1995. In 2011, roughly two-thirds of those with an academic profession were employed in computer sciences, computer engineering, electrical and electronics engineering, practical engineers and programmers in the information technology industries, and just one-third were employed in the other industries in the economy.

v Due to the uniqueness of the human capital, growth in employment in information technologies is based mainly on recruiting young employees completing a Bachelor’s degree in engineering or computers, or completing programming courses. The long duration of studies creates a gap between the timing of the growth in demand for employment and the growth in the supply of workers.

v The uniqueness of the human capital required in the information technology industries and the concentration of most of the employed persons possessing human capital of this type in these industries may increase the sensitivity of wages in these industries to external shocks. For instance, during the crisis in 2008–9, when there was a slowdown in global trade and real appreciation, companies in the industry were able to cope, inter alia, by decreasing real wages by a cumulative rate of close to 7 percent, compared to just 2.2 percent in manufacturing.

An article written by Dr. Yoav Friedman of the Bank of Israel’s Research Department outlines and analyzes the developments of employment, wages and profitability in the information technology industries in Israel—the electronics and software services and research and development industries (excluding the communications industry)—in the past 15 years. More than 190,000 people were employed in the information technology industries in 2011, constituting close to 9 percent of those employed in the business sector. Close to half of them were employed in the computer services industry, which is the largest among the information technology industries. The growth in the number of those employed and in the product of the computer services and research and development industries in the past 15 years are what has led to the growth of the information technology industries in the economy, while the electronics industry has maintained its relative weight regarding the number of employed persons, and its weight in business product has declined slightly in recent years.

One of the more interesting findings of the study is the growing uniqueness of the human capital (in aggregate terms) of those working in the information technology industries. Close to half of the workers in the information technology industries currently hold one of the following four professions: (1) systems analysts and those with a profession in the computer sciences; (2) computer engineers; (3) electrical and electronics engineers; and (4) practical engineers, technicians, and programmers. This is compared to just 30 percent in 1995.

The uniqueness of the human capital in the information technology industries is reflected in the long adjustment time between changes in demand for workers (for instance due to increased productivity) and the response of supply to these changes. One of the reasons for this is that about 65 percent of those with the aforementioned professions are currently employed in the information technology industries (see Table 1 below). The concentration of electrical and electronics engineers, computer science graduates, programmers and practical engineers in the information technology industries makes it difficult for these industries to expand at the expense of other industries, and the expansion of this industry is based mainly on young people, just entering the labor force after having completed studies for a relevant degree or completed an appropriate training course, joining the industry.

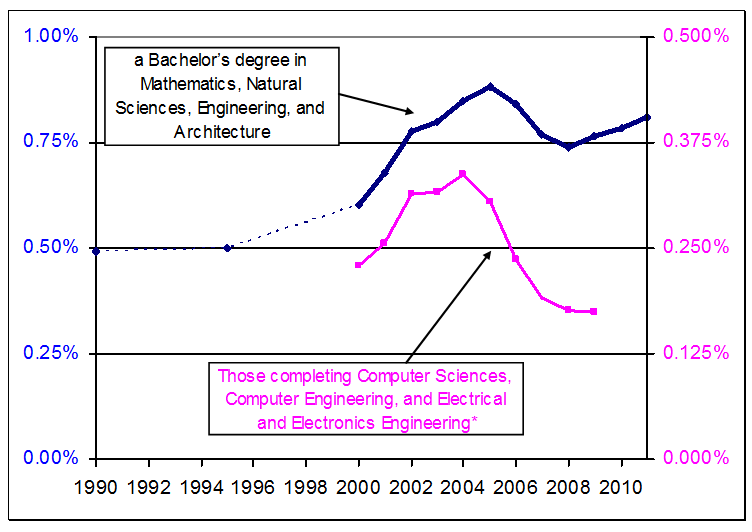

The article provides evidence of a lag of between five and eight years until the supply of workers adjusts itself to the sharp increase in demand. The number of those completing a Bachelor’s degree in computer sciences, computer engineering, and electrical and electronics engineering (as a percentage of the young population) reached its peak in 2004, more than 5 years after the jump in yield on studies in these professions occurred. It was only in 2006–8, five to seven years after the dot-com crisis, that there was a decline in the number of those completing a Bachelor’s degree in these professions (see Figure 1 below). It is also possible that the real appreciation of the shekel and the decline in global demand in 2008–9 contributed to the decline that took place in the number of candidates for studies in engineering and architecture, mathematics and natural sciences at the universities in 2010–11. The study also shows that the growth in the weight of employed persons with an academic profession in the information technology industries in the past 15 years—from 24 percent to 33 percent—is more significant than in the other principle industries, where it increased from 5.5 percent to just 9 percent.

The analysis in the article indicates that the uniqueness of the human capital in the information technologies industry and the concentration of most of those with the relevant human capital in employment in these industries may have ramifications regarding the development of wages in response to shocks. For instance, in 2008–9, when global trade declined and real appreciation of the shekel had a negative impact on the information technology industries, real wages in these industries declined by an aggregate rate of close to 7 percent, while they declined by 2.4 percent in the entire business sector (excluding the information technology industries) and by just 2.2 percent in the manufacturing industries (excluding the electronics industries).

Figure 1: Those completing a Bachelor’s degree in Mathematics, Natural Sciences, Engineering and Architecture, and Computers as a percent of the population aged 25–34.

* Not including those completing a degree in Computer Engineering and Electrical and Electronics Engineering at the academic colleges. SOURCE: Central Bureau of Statistics publications on higher education.

Table 1: Distribution of employment of computer and electronics engineers and practical engineers and programmers in the principle industries, 2011

(2011, in percent. Total employed persons in the economy in all professions appears in brackets)

*Including: systems analysts and those with academic professions in computer sciences, electrical and electronics engineers, computer engineers, practical engineers, computer technicians and programmers.

SOURCE: The author’s analysis of Central Bureau of Statistics labor force surveys.