- The Two-Pillar Reform in international taxation aims to ensure fair and efficient taxation of multinational corporations by addressing the challenges posed by the digital and global economy. These challenges include the ability of companies operating in one country to register their income and pay taxes in another country with lower tax rates.

- The first pillar focuses on taxing large and highly profitable multinational corporations, creating a new taxation right for market destination countries where the economic activity generating the profits took place. The second pillar establishes a global mechanism for an effective minimum tax rate of 15 percent, addressing the phenomenon of profit shifting and base erosion.

- The reform necessitates an examination of its potential impacts on Israel’s attractiveness as a destination for foreign investments, while also creating opportunities to increase tax collection and reduce the use of tax benefits.

The current international taxation system, designed over a century ago, is struggling to cope with increased globalization and the modern economy, where much business activity occurs in a virtual space without the need for physical presence. The international tax reform, led by the OECD, aims to address these challenges. It includes two main pillars designed to close gaps in the tax system in the digital age of the global economy. These changes are intended to ensure that the tax system is fairer and more efficient, and meets the needs of the modern economy. A new policy paper written by Dr. Sagit Leviner and Yehuda Porath of the Bank of Israel Research Department reviews the reform from a macroeconomic perspective, explains its components, and discusses its possible implications on investment promotion policies.

The first pillar of the reform focuses on taxing large and highly profitable multinational corporations. It transfers the right to tax a portion of the business profits generated by these companies to market destination countries where the final consumers of the companies’ products or services are located. Most of the affected companies are currently based in developed countries, so this pillar is expected to primarily transfer tax revenues from developed to developing countries. However, its impact on the global economy, as well as on Israel’s economy, is expected to be relatively small.

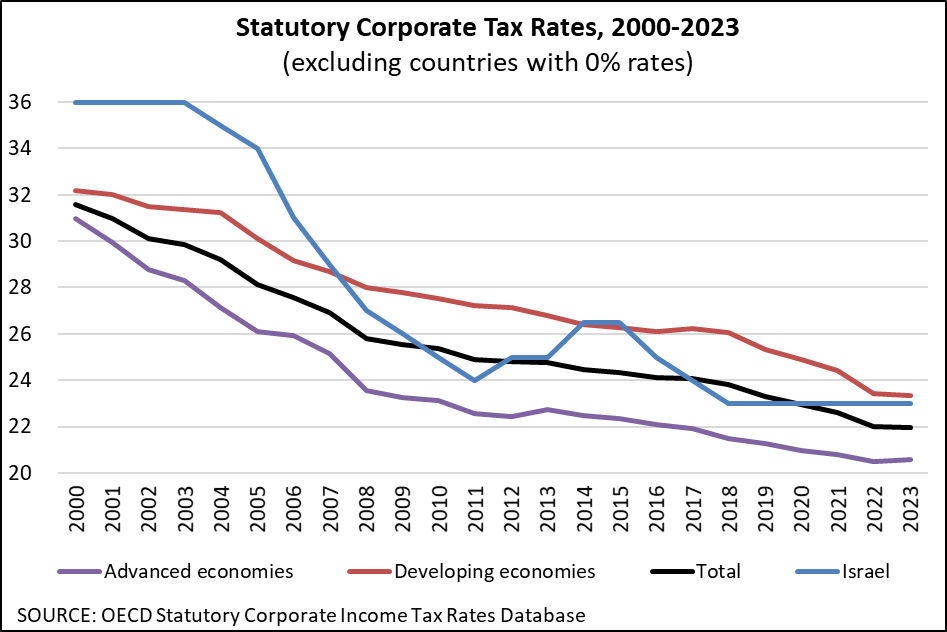

The second pillar establishes a global mechanism for an effective minimum tax rate of 15 percent for multinational corporations.[1] This pillar addresses the ongoing decline in corporate tax rates (“the race to the bottom”, see the figure below) and the profit shifting that has significantly eroded the tax base in recent decades. It does so by setting a limit on international tax competition. The mechanism operates by creating an additional taxation right in countries related to the company’s activities if a multinational corporation does not reach the minimum tax rate in the country where it operates. It is designed to ensure that multinational corporations pay minimum taxes regardless of where they operate. The scope of the second pillar is broader than that of the first, applying to a larger number of companies and potentially having a more significant impact on the global economy in general, and on Israel’s economy in particular.

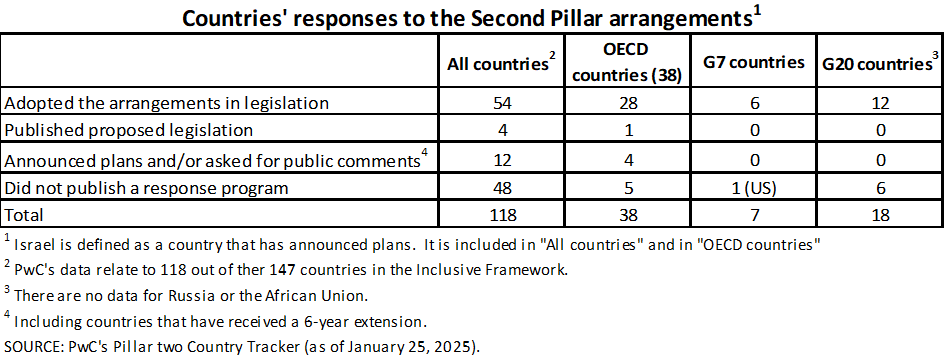

As of now, 147 countries have joined the Two-Pillar Reform in principle through the OECD’s Inclusive Framework. Of the 118 countries that have joined the Inclusive Framework and for which data is available in PwC’s databases, 58 countries have already published detailed plans for implementing the reform or adopted the second pillar arrangements in local legislation, and 12 others have announced plans related to the reform or sought public comments, including Israel. OECD and G20 countries are leading the implementation of the reform. However, there is still much work to be done to complete the implementation of the reform in all of the Inclusive Framework member countries. Given the US administration’s opposition to the reform, it is possible that the United States will slow down the reform or demand further examination. For example, a new Executive Order has declared that the international tax reform will not be implemented in the US, and has instructed the planning of countermeasures against countries that apply tax rules that discriminate against American companies.[2]

The reform has the potential to moderate international competition for attracting investments, thereby reducing the extent of tax incentives that Israel needs to offer to attract companies. Currently, the economic cost of these incentives is approximately 0.3 percent of GDP annually (around NIS 6 billion per year).[3] Reducing these incentives would increase state revenues, which is particularly important in the current period given the long-term increase in defense expenditures. Specifically, equalizing the global minimum tax rate presents an opportunity to reassess Israel’s investment promotion regime, with the aim to focus it on companies that provide special benefits to the economy: investments that create broader value than what is reflected in the company’s profits (“positive externalities”), or those that are of high value to the economy and where the investing companies have the ability to relocate from Israel.

Alongside the inherent benefits of the Reform, it is necessary to examine if and where it might reduce Israel’s attractiveness as a destination for foreign investments. Israel currently encourages investments primarily through a reduced corporate tax rate under the Encouragement of Capital Investments Law. Companies eligible for corporate tax benefits enjoy significantly reduced tax rates, which can be as low as 6 percent, compared to the statutory corporate tax rate in Israel of 23 percent. According to the Reform’s rules, if these companies pay an effective tax rate lower than 15 percent in Israel, other countries where these companies operate could tax them on the difference between 6 and 15 percent. Therefore, it is appropriate for Israel to impose a local effective minimum corporate tax of 15 percent, either through a supplementary local tax or by reducing existing benefits. To compensate, in cases where there is a special benefit from the activities of some companies, alternative incentives that comply with the Reform’s rules will need to be developed.

Beyond adjusting direct incentives where necessary, the potential reduction in international competition for companies through tax incentives highlights the need to improve the fundamentals of Israel’s economy by investing in human capital and infrastructure to enhance Israel’s attractiveness to investors. Recommendations for such measures, which will help maintain Israel’s attractiveness as a destination for foreign investments and support long-term economic growth, have been published as part of strategic plans submitted by the Bank of Israel to incoming governments, the latest of which was in January 2023.[4]

[1] Effective taxation primarily refers to taxes actually paid and does not take into account most types of tax benefits for companies.

[2] https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/the-organization-for-economic-co-operation-and-development-oecd-global-tax-deal-global-tax-deal/

[3] Israel Tax Authority (2024), Report of the Israel Tax Authority for the years 2021-2022 and preliminary data for 2023, Ministry of Finance, Chief Economist’s Office, Israel.

[4] See link: https://www.boi.org.il/en/communication-and-publications/press-releases/the-bank-of-israel-s-program-to-accelerate-economic-growth-recommended-strategic-pillars-of-action-for-the-government/