- The Houthi attacks on vessels in the Red Sea, which began in November 2023, led to the diversion of shipping routes between Asia/Oceania and the Mediterranean/Europe from the shorter route through the Red Sea to the longer route around the Cape of Good Hope in Africa. Despite this change, there was no significant impact on Israeli imports from Asia, and import prices did not rise.

- Unlike Israel, the diversion of shipping routes from the Red Sea to the Cape of Good Hope was accompanied by a temporary decline in imports from Asia to other OECD countries bordering the Mediterranean. Globally, the diversion of shipping routes was also accompanied by a temporary decline of about 10% in the value of trade usually transported through the Red Sea, and an increase in maritime transport rates from China to Europe and the Mediterranean.

- In the second phase, during February-March 2024, several changes occurred: freight rates from China to the US also rose, while the increase in freight rates from China to Europe and the Mediterranean moderated, and trade usually transported through the Red Sea recovered. These dynamics are consistent with a shift in maritime transport capacity (ships and containers) from various shipping routes worldwide to the routes between Asia/Oceania and the Mediterranean/Europe, to compensate for the lengthening of the shipping routes.

Starting in late November 2023, the Houthis began attacking vessels in the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea. These attacks threaten a major international shipping route between South and East Asia and Oceania (hereinafter Asia/Oceania) and the Mediterranean and Europe. In 2023, about 22% of the world's maritime container traffic (in terms of weight) passed through the Suez Canal in the northern Red Sea. In response to the attacks, shipping companies diverted the routes of cargo ships from the shorter route through the Red Sea to the shipping route that circumnavigates the Cape of Good Hope in Africa. The potential impact of diverting shipping routes from the Red Sea to the Cape of Good Hope is significant, especially in the Mediterranean region, due to the longer shipping distances. For example, the shipping distance between China and Israel increased by about 114% following the diversion of the routes.

An analysis conducted by Haggayi Etkes of the Bank of Israel Research Department and Nitzan Feldman of the University of Haifa used up-to-date and detailed Israeli and international data on trade in goods to examine the impact of the attacks on the value of trade.

Key findings:

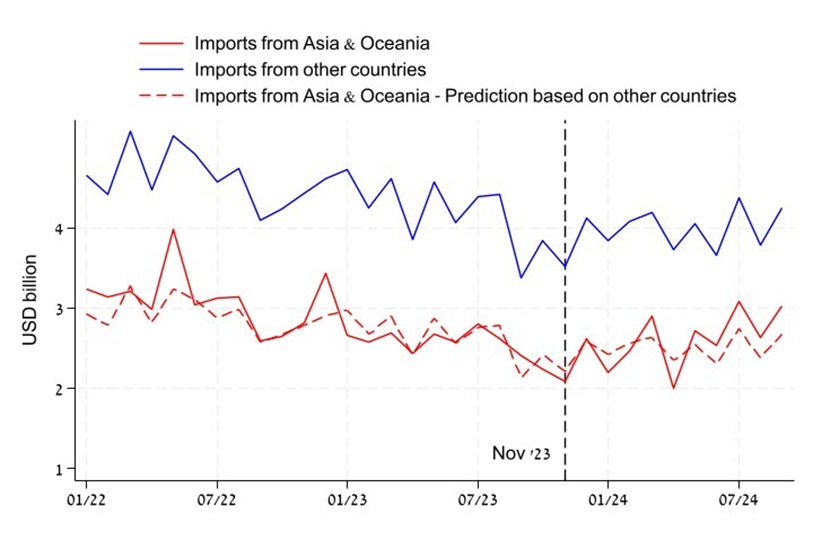

The composition of Israel's foreign trade indicates that the impact on Israeli exports may be limited because only about $3.4 billion worth of goods, which is about 5% of Israel's total goods exports, are transported by sea to Asia and Oceania. In contrast, maritime imports from these regions to Israel amounted to about $20 billion in 2023, which is about one-fifth of total civilian imports. However, the analysis found that total Israeli imports from Asia and Oceania did not decline significantly due to the Houthi attacks—either in absolute terms or relative to imports from the rest of the world (Figure 1). Import prices to Israel, which include transportation and insurance costs, also did not rise significantly in the first half of 2024. Therefore, the impact of the Houthi attacks and the subsequent diversion of shipping routes on Israel’s foreign trade was likely limited.

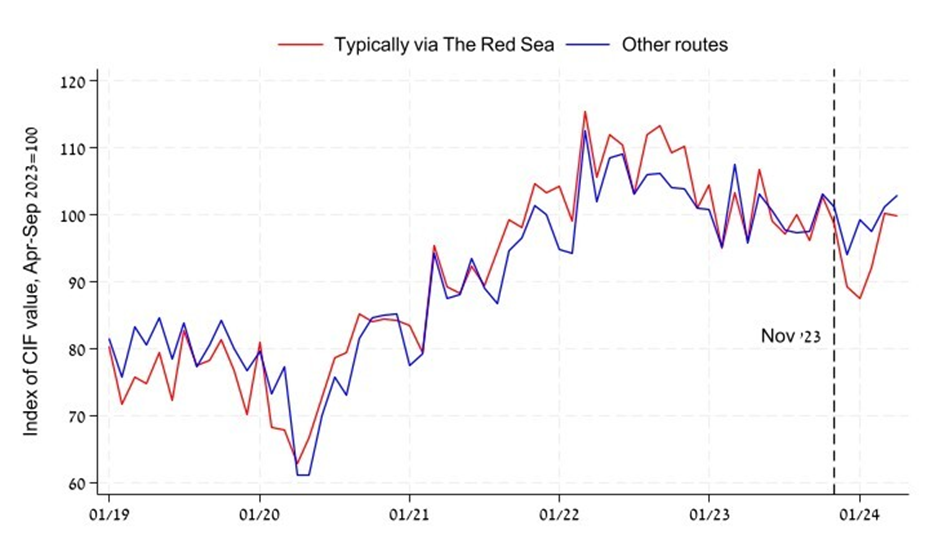

In contrast to Israel, the Houthi attacks had a significant but temporary impact on the volume of imports from Asia, Oceania, and East Africa to other OECD countries in the Mediterranean (Greece, Turkey, Italy, France, and Spain). These imports declined in December 2023 and recovered in most of these countries in the spring of 2024. The Houthi attacks on vessels in the Red Sea affected not only the maritime trade of Mediterranean countries but also global maritime transport. Initially, the diversion of the shipping route from the Red Sea caused an increase in transport rates from China to Europe and the Mediterranean, and a decrease of about 10% in the value of trade between pairs of countries for which the shorter route through the Red Sea passes, while trade between other pairs of countries did not decrease significantly (Figure 2).

In the second phase, in February-March 2024, there was an increase in maritime freight rates on routes that do not pass through the Red Sea, such as from China to the west coast of the United States, alongside more moderate rates on shipping routes from China to Europe and the Mediterranean. In addition, trade between countries whose maritime trade is usually transported through the Red Sea recovered (Figure 2). This increase in freight rates from China to the United States, the moderation of freight rates from China to Europe, and the recovery of trade usually transported through the Red Sea, are consistent with a reallocation of maritime transport capacity, such as ships and containers, from the trans-Pacific shipping route, and likely other shipping routes, to the shipping routes from Asia/Oceania to Europe and the Mediterranean.

Evidently, Israel—despite being the declared target of the Houthi attacks—stands out as an exception and did not suffer a significant decrease in imports from Asia/Oceania following these attacks. There are several possible reasons for Israel's exceptional situation. First, total civilian imports to Israel decreased following the outbreak of the war—before the Houthi attacks—so it is possible that the decrease in imports from Asia/Oceania was masked by the overall decrease in import value. Another possible explanation is that the ZIM shipping company was quick to divert its vessels to an alternative shipping route that bypasses Africa, which caused the decrease in imports to Israel to be earlier and more gradual than the decrease recorded in other countries. Additionally, Israel's exposure to the blockage of the Red Sea route is relatively moderate because maritime imports account for a lower proportion of total imports from Asia/Oceania to Israel (65%) than the corresponding proportion to some other Mediterranean countries such as Portugal (78%) and Greece (89%). A more comprehensive examination of the reasons for Israel's exceptionality is beyond the scope of this analysis.

Figure 1:

Importsa to Israel from Asia-Oceania, and Imports from Other Countries, 2022–2024 (US$ billion)

a Civilian imports, excl. energy products, by country of origin.

SOURCE: Based on Central Bureau of Statistics.

Figure 2:

Value of Reported Global Tradea by Typical Shipping Lane: Red Sea or Other, 2019–2024 (index of import value, March–September 2023 avg. = 100)

a Based on reports from 65 countries reporting on their foreign trade up to April 2024 to Comtrade.

SOURCE: Based on Comtrade data.

Click to download as PDF Click to download as PDF