- To view this message as a file click here

- The basic skills level of the Israeli population in 2022 was about 0.3 standard deviations lower than the OECD average in all knowledge areas—literacy, numeracy, and adaptive problem solving. The gap was particularly prominent in Arab society—roughly one full standard deviation relative to the OECD average.

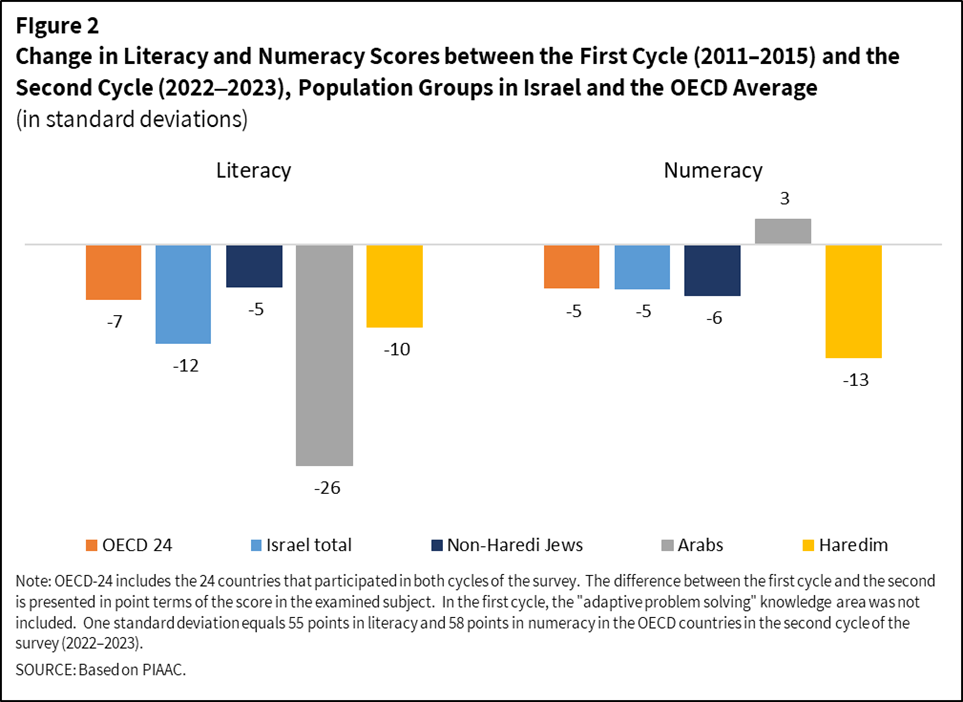

- Alongside the general decline in reading achievements globally in the past decade, the literacy gaps between Israel and the OECD average widened due to a marked decline in literacy skills among the Arab population. Numeracy skills remained virtually unchanged, and the gaps between Israel and the OECD average remained steady.

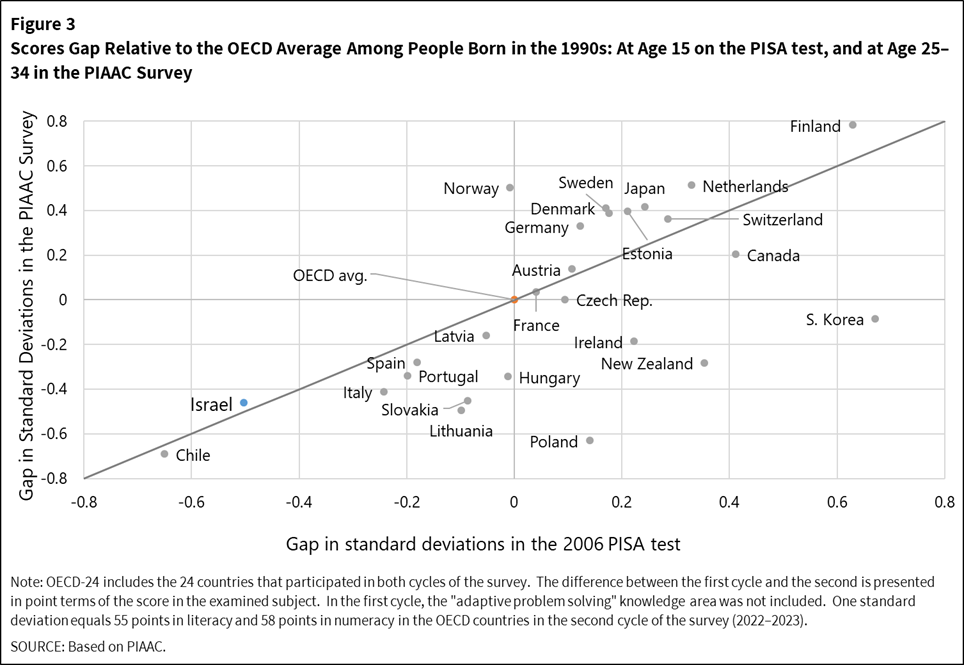

- A significant part of the skills differences between Israel and the OECD average are due to large gaps during childhood and adolescence, as shown by PISA test scores in secondary school. The high rate of those with post-secondary education in Israel is not translated into closing the skills gaps relative to the OECD average.

- The skills of Israeli workers are lower than the OECD average, particularly in lower-skilled professions and industries.

The PIAAC survey is an international project to assess basic skills among people aged 16–65 in the areas of literacy, numeracy, and adaptive problem solving. Israel participated in the survey for the first time in 2014–2015 (in the latter part of the cycle that took place between 2011 and 2015), and recently took part in the cycle that was conducted in 2022–2023. The survey’s contribution to policy analysis is due to the high correlation between the population’s skill level and the country’s per capita GDP. A new analysis by Sefi Bahar and Elad DeMalachof the Bank of Israel Research Department presents initial findings with regard to the skills of the Israeli population by international comparison based on the 2022–2023 survey.

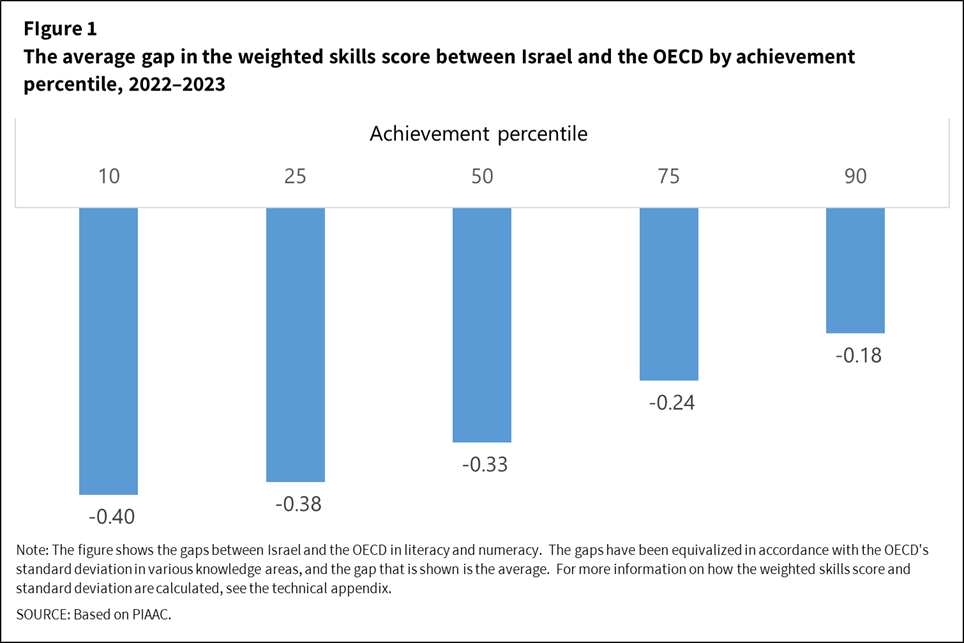

Skill scores in Israel are 15 points (approximately 0.3 standard deviations) below the OECD average, with significant differences between population groups. The scores of the Arab population are significantly lower, with a gap of 45-60 points (a whole standard deviation) compared to the average score among non-Haredi Jews. The scores of the Haredi (ultra-Orthodox) population are about 10 points (0.2 standard deviations) lower than the average among non-Haredi Jews. The score gaps between Israel and the OECD are prominent and noticeable across different segments of the population: men and women, adults and young people, as well as individuals with varying levels of education. Particularly notable gaps in scores were found among the lower skill percentiles (Figure 1). In other words, while the scores of Israelis with high skill levels are only slightly lower than those of their OECD counterparts, those with low skill levels received much lower scores than their OECD counterparts.

A comparison between the survey cycles, presented in Figure 2, shows that the skills gap between Israel and the OECD average increased between the 2011–2015 and 2022–2023 surveys, mainly due to a significant decline in literacy among the Arab population (a 26-point decline, about half a standard deviation), as well as a decline in the Haredi community, while the change in the non-Haredi Jewish community was similar to the OECD average. In contrast, there was no change in the numeracy gaps between Israel and the OECD average.

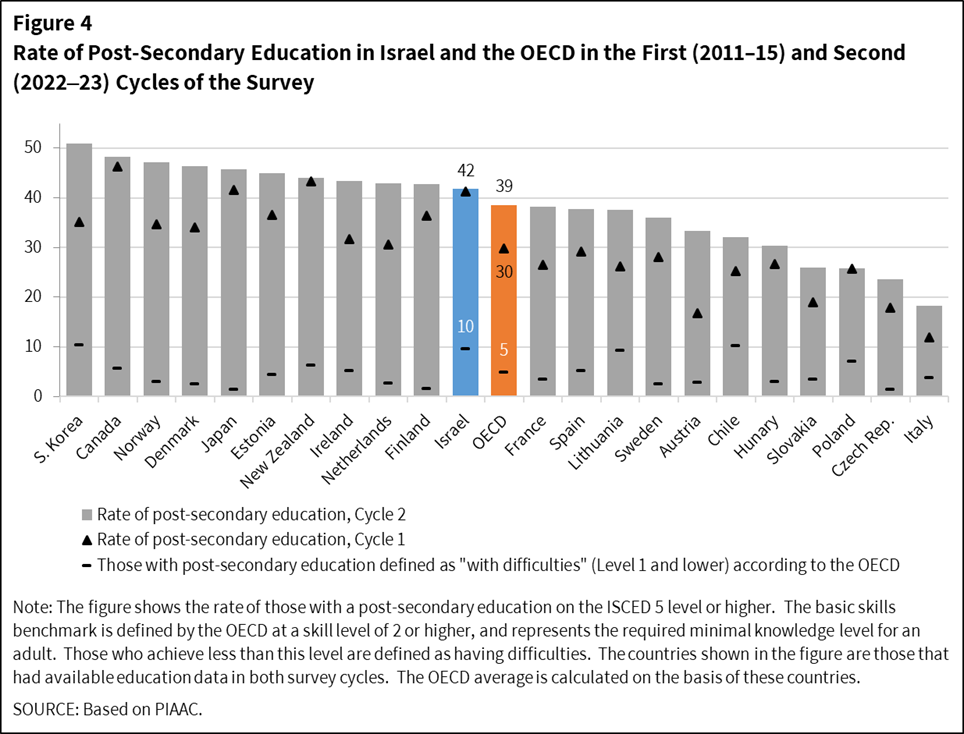

There are already marked gaps in human capital between Israel and the OECD at early ages, and they remain significant throughout the lifespan. Figure 3 illustrates how the score gaps observed at age 15 (in the 2006 PISA tests) remained similar at ages 25–34 (in the PIAAC tests in 2022–2023). The skills gaps between Israel and the OECD are significant despite the fact that the rate of Israelis with post-secondary education is higher than the OECD average. However, the gap in Israel’s favor in the rate of those with higher education narrowed from 12 percentage points in the 2011–2015 survey to just 3 percentage points in the 2022–2023 survey. In addition, 10 percent of those with post-secondary education in Israel lack the minimal level of knowledge required of an adult—an anomalous rate compared with the OECD (Figure 4). Another factor that may explain the skills gaps between Israel and the OECD average is the higher rate of skills erosion as adults age. The analysis shows that skills erosion with increasing age is more prominent in Israel than in the OECD among those born in the 1960s and 1970s.

An examination of the labor market shows that skills gaps are particularly prominent among those employed in low-skill industries and occupations For instance, the skills gap among those with an academic occupation is about 0.3 standard deviations, while the gap among professional workers in manufacturing is about 0.5 standard deviations. In the information and communications industry, the skills gap is just 0.15 standard deviations, while in the construction and transportation industries, it is about 0.6 standard deviations.

In conclusion, the achievement gaps between Israel and the OECD indicate significant policy challenges in the area of human capital. The gaps that were observed in the Israeli education system at age 15 continue and are affecting the performance of adults, while the high rate of those with higher education is not translated into a narrowing of the gaps between Israel and the OECD. The higher skills erosion in the older population in Israel raises the need to invest in learning and skills improvement throughout the lifespan, from the education system through higher education to professional training at older ages. This will provide skills that are relevant to the changing labor market.