- In the past four years, the number of Palestinians residing in the West Bank and working in the Israeli economy has doubled, reaching around 92,000 in 2014. This increase includes both workers with a permit and those without a permit.

- The number of employee posts filled by Palestinians in the construction industry doubled in the past two years, reaching about 15.3 percent of employee posts in the industry. This increase accounts for most of the growth in employment in the industry, as the number of posts held by Israeli and foreign workers was virtually unchanged.

- Alongside the marked increase in the number of legal Palestinian workers, the stability and availability of their employment increased as well. This contributes to the efficiency in industries employing them, and diminishes one of the advantages that foreign workers held over Palestinian workers in the past decade.

A. The expansion of Palestinian employment in the Israeli economy

In the past four years, the number of Palestinians residing in the West Bank and working in the Israeli economy has doubled, and in 2014 it reached around 92,000—about 2.2 percent of total employees in the Israeli economy. This estimate is based on labor force surveys of the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS), and is in line with Israel Tax Authority data on work permit-holding Palestinian workers (Table 1).[1] The main increase in employment derived from the increase in the number of workers holding work permits—according to the estimate in the PCBS labor force survey, it reached 59,000 in 2014, and increased due to government policy intended to increase the supply of workers in the construction and agriculture industries as well as to assist the Palestinian economy. At the same time, employment of Palestinians without work permits also increased, which indicates that Palestinian demand for employment in Israel is greater than the number of permits, and that there is considerable demand in Israel for Palestinian workers, mainly in the construction industry. The size of Palestinian employment in the Israeli economy is expected to continue to grow in the foreseeable future.

Table 1

Employment and wages for Palestinians employed in Israeli economy, 2007–14

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

||||||||||

Employment, ‘000

Number of workers in average month, per ITA |

31 |

34 |

36 |

39 |

41 |

45 |

|||||||||||

Number of workers in average week,

per PCBSa |

38 |

41 |

47 |

46 |

53 |

60 |

82 |

92 |

|||||||||

Of which: Workers with a permit |

21 |

25 |

29 |

31 |

32 |

39 |

49 |

59 |

|||||||||

Workers without a permit |

17 |

16 |

18 |

15 |

20 |

22 |

33 |

33 |

|||||||||

Share employed in construction industry |

37% |

37% |

38% |

44% |

47% |

47% |

48% |

||||||||||

Average monthly wage (‘000 NIS): | |||||||||||||||||

Workers with a permit , per ITA |

2.6 |

2.6 |

2.8 |

3.2 |

3.4 |

3.6 |

|||||||||||

Workers with a permit, per PCBS |

2.4 |

2.5 |

2.6 |

2.9 |

3.1 |

3.3 |

3.5 |

||||||||||

Workers without a permit, per PCBS |

2.0 |

1.8 |

2.2 |

2.4 |

2.7 |

2.6 |

2.7 |

||||||||||

Sources: Israel Tax Authority (ITA); Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS).

a Excluding residents of Eastern Jerusalem and holders of foreign passports. Those groups are included in Palestinian Labor Force Surveys.

b Monthly wages per PCBS were calculated by summations of the individual product of daily wages and working days.

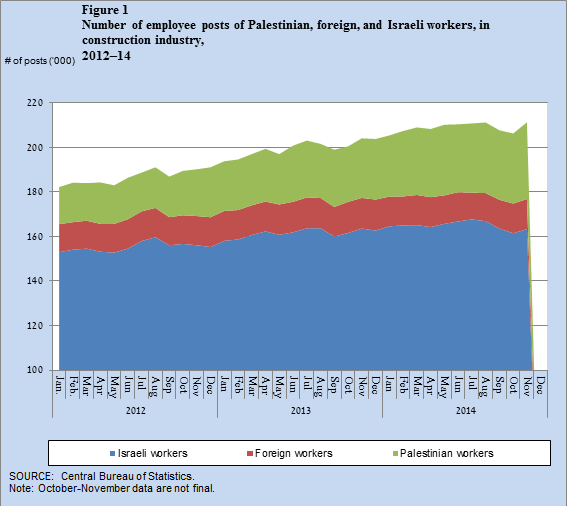

About half of the Palestinians who worked in 2013 in Israel’s economy were employed in the construction industry. Figure 1 indicates that the main increase in the past two years (2013–14) in reported employment (employee posts) in this industry derived from growth in the number of Palestinian workers, as the number of Israeli and foreign workers did not change markedly. The actual increase in Palestinian employment was even greater, as the industry also increased the number of workers who do not hold a work permit. The increase in Palestinian employment in the construction industry[2] reduces the incentive for investment in capital, in improved technology, and in workforce training.[3] To the extent that the increase in Palestinian employment is not accompanied by an increase in activity in the industry, it may adversely affect employment and wages of similar Israeli workers.

B. Regulation of the Palestinian employment in the Israeli economy

Employment quotas of Palestinians within the borders of the State of Israel are determined separately for each economic industry, and are set by government decision and in accordance with the recommendation of Government ministries and the defense establishment. In contrast, there are no quotas for work permits in Israeli settlements and industrial zones in the West Bank. A Palestinian worker is entitled to every work condition that a similar Israeli worker is entitled to by law and by relevant collective agreements. For example, a Palestinian worker in the construction industry is entitled to the minimum wage set in the industry’s collective agreement. These agreements are intended to ensure the rights of Palestinian workers and to minimize the negative impact on similar Israeli workers.

However, as the State Comptroller has warned[4], in actuality Palestinian workers’ rights are only exercised to a limited extent. This derives, to a certain extent, from the only partial awareness of Palestinian workers of their rights: Palestinian labor force surveys indicate that among Palestinians working with a permit in the Israeli economy, only a very small share claimed that they are employed through a contract and are eligible for pension allowances, sick days and vacation days—and this is even though the Population and Immigration Authority (PIA) sets such funds aside, as required by the law, and even though workers in the construction industry are covered by collective agreements.[5] Informing Palestinian workers of their rights may enhance the utilization of these rights. Table 2 indicates that the state of workers without work permits is even more severe.

As the Israeli and Palestinian economies are differentiated by their level of economic development, there is a gap between the wage for a Palestinian worker in the Israeli and in the Palestinian economies. The minimum wage in Israel (NIS 198 per full work day) is higher than the average wage in the West Bank, which in 2014 was about NIS 91 per day. This gap creates an economic incentive for Israeli intermediaries, or the Palestinian heads of worker groups, to collect intermediation fees for a work permit in Israel. Such collection is made possible because the procedures provide the Israeli employer with the power, as they determine that the employer requests the permit for work in Israel on behalf of a specific Palestinian worker, and the employer can replace him by requesting a permit for another worker. The salary per worker that is reported by workers in the Palestinian labor force surveys is indeed similar to the wage reported to Israeli authorities.[6] Nonetheless, anecdotal evidence suggests that workers pay intermediation significant fees.

Permits for employment in Israel are granted to Palestinians of a specific age and older[7], and who are married. Therefore, permit holders are relatively older than those without a work permit, and an overwhelming majority is married, while among those without a work permit only about 50 percent are married. The average daily wage of workers without permits was around NIS 158 in 2013, and was markedly higher than the average daily wage in the West Bank (NIS 87), but lower than the average daily wage of workers holding work permits (NIS 186). The gap in average monthly wages is even greater, because workers without work permits worked fewer days per month.

Table 2

Characteristics of Palestinian workers in Israel: Those holding a permit and those not holding a permit, 2013

Holding permit |

Not holding permit | |

Average age (years) |

38.2 |

28.8 |

Percentage married |

90% |

48% |

Education (years of study) |

9.6 |

10.1 |

Percentage living in villages |

38% |

39% |

Share of males |

99% |

99% |

Daily wage (NIS) |

186 |

158 |

Number of workdays in month |

19.0 |

17.1 |

Reporting having a written work contract/collective agreementa |

2% |

1% |

Reporting having a verbal work contracta |

40% |

27% |

Reporting having no work contracta |

58% |

73% |

Reporting having funds set aside for pensions |

4% |

1% |

Reporting entitlement to sick days and vacation daysa |

11% |

1% |

SOURCE: Based on Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics.

a This question was answered by about 78 percent of permit holders, and about 60 percent of those not holding permits. | ||

C. The improvement in availability of Palestinian workers

Another notable phenomenon is indicated by the data in Table 3: the stability of employment among Palestinian workers holding permits increased. In 2006, only about one-third of them remained for two years with the same employer, and in 2012 that share increased to two-thirds. This share is somewhat lower than the share among Israelis who work in companies that employ Palestinians. The average number of annual work months of Palestinian workers also increased markedly, and approached the figure among Israeli workers in companies that employ Palestinians. In addition, in the second half of 2014, the Ministry of Defense increased the number of overnight-stay permits in Israel, from 10,000 to around 14,000, increasing the availability of Palestinian workers for work in Israel. A comparison between Israeli and Palestinian workers in companies that employ Palestinians finds that between 2008 and 2009—that is, the beginning of the global economic crisis—the share of Israelis working alongside Palestinians for two consecutive years declined by 15 percentage points, while the employment rates of Palestinians remained stable (Table 3). This phenomenon indicates that even during the period of the crisis, Israeli employers preferred to keep Palestinian workers.

The increase in the stability of employment of Palestinian workers and in their availability is an additional reason for an increase in demand by Israeli employers for Palestinian workers. The increase in the stability and availability of Palestinian labor has positive ramifications on industries employing Palestinians, as it reduces the waste of resources inherent in repeated searching and training of new workers, and in the uncertainty of workers’ availability. Such waste was created in the past, as the availability of Palestinian workers was affected by fluctuations in political-security relations between Israel and the Palestinian Authority. It should be noted that in recent rounds of hostilities, including the period in which Operation Protective Edge took place, the defense establishment allowed most Palestinian workers to continue to enter Israel on a regular basis. Such a policy diminishes one of the advantages that employment of foreign workers held over employment of Palestinian workers in the past.

Table 3

Employment persistence and availability: Israelis and Palestinians, 2006–12

(Males whose employment was reported to the Israel Tax Authority, excluding public sector workers)

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 | ||

Share of workers employed for two years at companies that employ Palestinians (percent) |

Palestinians |

33 |

52 |

59 |

60 |

60 |

67 |

67 |

Israelis |

73 |

74 |

75 |

59 |

74 |

78 |

72 | |

Average number of months of work per year at companies that employ Palestinians |

Palestinians |

5.9 |

7.8 |

8.2 |

8.6 |

8.7 |

8.7 |

8.5 |

Israelis |

6.8 |

7.1 |

7.2 |

8.5 |

7.3 |

7.5 |

8.2 |

SOURCE: Based on Israel Tax Authority data.

The persistence of Palestinians in work in Israel comes with an increase in wage; the reported wage of Palestinians employed in Israel with the same employer from 2006 through 2012 was about 14 percent higher than the average monthly wage of Palestinians who began to work in Israel in 2012. This rate of growth is lower than the rate of wage increase of Israelis who remained in their place of work in companies that employed Palestinians (27 percent).There are marked wage gaps between Palestinian and Israeli workers in those companies. Part of the gap in monthly wages derives from the difference in labor inputs. For example, in 2012, an Israeli employee in the construction industry worked 37.1 hours per week, while a Palestinian employee worked 29.1 hours per week. It is also plausible that Palestinians’ professions are different than the professions of Israeli workers, and with a lower wage (Table 4).

Table 4

Salary of Israelis and Palestinian workers, by length of tenure at place of work, 2012

(Salary in NIS thousands; Males whose employment was reported to the Israel Tax Authority, excluding public sector workers)

Years of tenure |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 | |

First year of work |

2012 |

2011 |

2010 |

2009 |

2008 |

2007 |

2006 | |

Workers employed at companies that employ Palestinians |

Palestinians |

3.7 |

3.9 |

4 |

4 |

4.1 |

4.1 |

4.2 |

Israelis |

8.6 |

9.1 |

9.5 |

10 |

10.4 |

10.8 |

10.9 | |

Workers at other companies |

Israelis |

8.8 |

9.6 |

10.2 |

10.7 |

11.2 |

11.8 |

12.6 |

SOURCE: Based on Israel Tax Authority data.

[1] Employment in Israel is important to the Palestinian economy: According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS), in 2014, Palestinians working in the Israeli economy made up about 11.7 percent of the Palestinian workforce in the West Bank, and their total wages in 2013 were equal to 12.3 percent of West Bank GDP. PCBS estimates referred to here do not include residents of Eastern Jerusalem and holders of foreign passports, though those groups are included in Palestinian labor force surveys.

The Israel Tax Authority’s estimate of the number of workers holding a permit is different than the parallel estimate of the PCBS, because each of those groups uses a different unit of measurement: the Israel Tax Authority (ITA) refers to the number of workers in an average month, while the PCBS refers to the number per average week. This means that if a worker holding a permit worked one week in a given month, there is a probability of 1 of being included in ITA data and a probability of 25 percent of being included in PCBS data. Another possible explanation is underreporting to the ITA—Israelis who employ Palestinians in Judea and Samaria only partially reported that, as Israeli labor laws apply to that area in only a partial manner and the reporting obligation was only imposed in 2009.

[2] In September 2014, the government decided to increase the number of permits for Palestinian workers by 4,600.

[3] Proof of substitution between Israeli and foreign workers can be found in the report by the Committee for Regulation, Supervision, and Enforcement in the Employment of Palestinian Workers in Israel (2011), Chapter 5 of the Bank of Israel Annual Report, 2012 (pp: 79–82), as well as in the following research papers: Gotlieb, D. and S. Amir (2005), “Entry of foreigners and rejection of locals in Israeli employment”, Planning Research and Economics Administration in the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Labor, and Zussman, N. and D. Romanov (2003), “Foreign workers in the construction industry: the current situation and policy ramifications”, Bank of Israel Discussion Papers.

[4] State Comptroller Report 65a, 2014, “Employment of Palestinian workers in Israel’s construction industry”.

[5] The partial awareness is probably related to the fact that transfers in respect of social allocations are only carried out once a year.

[6] The Population and Immigration Authority (PIA) is working to switch to a regime in which Israeli employers will pay the gross wage to the PIA, which will then transfer the net amount to the worker’s bank account, thus verifying that such worker’s terms do not differ from what is set by law and by relevant collective agreements. Such a regime has been recommended by the OECD and by the State Comptroller (State Comptroller Report 65a, 2014), and is similar to the regime in place until 1995.

[7] The minimum age for receiving a work permit declined from 30 in 2010 to 24 in 2014.