Main points of the analysis

The objective of this analysis, conducted by the Bank of Israel Research Department, is to provide a practical analytical framework for specifying the expected impact of the Swords of Iron war on relative prices in the Israeli economy, focusing on an important test case: the food industry. On the demand side, we analyze the war’s impact on the level, elasticity, and composition of demand for products and services. On the supply side, we discuss the effects on firms’ cost structure (which in turn is affected by changes in the availability of raw materials, commodities, and labor input, as well as changes in production technology) and on the labor market. In the food industry, the analysis leads to the conclusion that the war is creating some upward pressure on consumer prices in the short and medium terms. Initial empirical evidence based on credit card expenditure data and a new and rapid daily index of food process (excluding fresh fruits and vegetables) developed by the Bank of Israel support this finding.

- Introduction

The war that broke out on October 7, 2023 posed significant challenge for the Israeli economy. This analysis focuses on one of the dimensions of this challenge: the war’s effect on relative prices in the economy.[1] The analysis takes a microeconomic approach, and focuses on the food industry due to its economic importance and its significant weight in the Consumer Price Index (about 12 percent of the consumption basket).[2] However, the analytical framework presented here can be implemented in other industries as well.

The war is significantly affecting the terms of demand and supply in the industries. Despite some similarities, this impact is markedly different from what the economy experienced during the COVID-19 crisis or during previous military engagements of the past decade. An international comparison is also challenging, since it is hard to find economies that have undergone a similar event in recent years that have similar basic characteristics to those of Israel.

As such, this paper presents an analytical framework for methodically analyzing the war’s impact on three basic market forces that determine the change in the consumer price level: demand, the structure of costs, and the intensity of competition. In Section 2 below, we present the expected impact of each of these factors in general and specifically in the food industry. As we show, in the food industry, most of the factors act in the direction of upward pressure on prices. In Section 3, we present initial data indicating a significant increase in food expenditures during the war, which are based on data regarding credit card expenditures on food products, alongside a new rapid index of food prices at the retail chains, developed as part of the framework. These provide initial evidence of an increase in demand and an increase of about 2 percent in the average prices of the food basket (excluding fruits and vegetables) in the weeks since the outbreak of the war.

- The war’s impact on market conditions

- Demand

The war affects demand through three main channels: the effect on the level of demand, the effect on the elasticity of demand, and demand alternatives—the potential diversion of demand from the private to the public sector.

2.1.1. Changes in the level of demand

The war is expected to lead to a significant decline in private demand for many goods and services. First, security uncertainty is accompanied by economic uncertainty that may cause many households to tighten their purse strings and reduce consumption. Second, many people have been mobilized for reserve duty and can therefore not consume as normal. Third, the public atmosphere and the shock due to the events of October 7 do not encourage consumption as normal. However, the effects of these factors are not uniform across industries, and will be only limited in some areas.

The impact on the food industry: Public demand for food in the retail segment (supermarket chains) is expected to large be immune from the effects of the war, and even to increase to some extent. At the beginning of the war, this demand intensified as the public stocked up on food products in view of the security situation—a factor that has had a weaker impact over time. In addition, demand for food at supermarkets is supported by the public’s greater tendency to eat at home rather than outside the home, at work, at restaurants, or at events.[3] These activities, which are not included in the food index that we examine, are declining, which in turn is due to security concerns, negative consumer sentiment toward recreation and leisure activities, and households’ desire to cut back on unnecessary expenses.

2.1.2. Changes in the elasticity of demand

The war may have an impact not only on the level of demand, but also on its elasticity. Insofar as certain population groups are removed from the normal computation of demand due to the war situation, the effective elasticity of demand is dictated by groups that continue to consume the product or service.[4] Insofar as these groups are less sensitive to price, the industry will serve a relatively small group of consumers whose demand is quite rigid. While the decline in the level of demand puts downward pressure on prices, its rigidity works in the opposite direction (as long as there is an impact on the supply side), and may moderate those pressures. Under certain circumstances, it may even be strong enough to lead to price increases.[5]

The impact on the food industry: In general, we do not expect a significant change in the elasticity of demand for food products during the war. Certain factors are contributing to the increased rigidity of demand. Stocking up with food is considered an existential need, whether for household consumption or to provide for reserve soldiers. In addition, the composition of demand is changing, and population groups that customarily eat outside the home and who are not replacing this activity with cooking and eating at home are being added to it. Insofar as this group includes young consumers with high income who live in large urban centers, these will purchase food at neighborhood groceries or in other more expensive formats, and will demonstrate an only limited readiness to invest time and resources in searching for cheaper alternatives.[6]

In contrast, there are also factors that work to increase the elasticity of demand. The negative consumer sentiment inherent in the concern over losing income will lead some households to invest greater efforts in searching for cheaper alternatives to the well-known food brands. In addition, furloughing of employees or a decline in the level of business activity for some households will enable them to invest more time into finding such alternatives.

2.1.3. Diversion of demand

In some areas, government or other institutional demand is expected to replace and compensate for the decline in private demand. For instance, the government has to equip and feed a very large volume of reserve forces, as well as support people who have been evacuated from combat areas.

The way in which the government is expanding its activities on the demand side is also important for understanding the pressures on price levels. In certain fields, the government will use its large bargaining power to purchase goods and services at a lower price, and in other areas it may show less sensitivity to prices. The impact of the volume of government activity on the private consumer’s bargaining power is also complex, and may act differently in different contexts. In addition, while the decline in private demand is immediate, the additional demand from the government is more gradual, and its effect on price levels is therefore felt in the medium term rather than immediately.

The impact on the food industry: The war has led to some diversion of demand for food from the private sector to the public sector. Reserve soldiers do not eat at home, but in contrast, the government must provide them with food. The increase in the intensity of additional security agencies such as the Israel Police will also lead to an increase in demand for food through the institutional market. This demand is expected to compete, to some extent, with demand in the private sector, and to moderate downward pressure on prices in the industry insofar as aggregate demand for food products (of the private sector and the government combined) increases.

Now that we have finished the discussion on the war’s effect on the demand side, we will discuss its impact on the supply side while separating between two aspects: the effect on the cost structure, and the effect on the intensity of competition.

- The cost structure

Firms’ cost structure may be impacted during a war as a result of three potential factors: an increase in input prices or impairment of their availability; changes in the supply of labor; and an impact to production technology.

2.2.1. Input prices and availability: goods and physical raw materials

Since the crisis is not global, it will be possible to continue importing most of the inputs required for domestic production activity.[7] However, there are factors impeding imports. The decline in the volume of maritime and air traffic, as well as more expensive or less attainable shipping insurance to Israel are having a negative impact on the domestic cost structure. In addition, the depreciation of the shekel, should it persist, makes the shekel prices of commodities and raw materials more expensive.[8]

The value chain includes links that are physically located in Israel. The mobilization of reserve soldiers and the impact to civil society, alongside a shortage of Palestinian and foreign laborers in view of the war make it more difficult for various suppliers and for companies lower down on the chain. An analysis of the war’s impact on a specific sector must therefore include a mapping of that sector’s suppliers, their geographic location, and their condition.

The impact on the food industry: The war’s effects on input prices and availability are marked throughout the value chain in this industry. The war has led to a direct and broad impact on fresh agricultural produce.[9] Beyond the impact to the supply of fresh fruits and vegetables in the markets (which are not included in the food price index that we will present below), there is also an impact to other food categories that use fruits and vegetables as production inputs, such as frozen vegetables and preserved foods. The ability to compensate for the decline in availability of fresh vegetables in the retail segment, for instance through imports from Turkey or Jordan, is limited – partly due to supermarkets’ concern over consumer boycotts. The import of vegetables as a production input is expected to be less sensitive to this aspect.

Most fresh agricultural produce is produced in Israel, with the exception of grains and oils that are imported from abroad. To the extent that the war continues and the decline in the volume of maritime traffic persists, inventory limitations may weigh down on the cost structure of many firms in the food industry. The import of finished food products to Israel is affected in a similar manner.

2.2.2. Supply of labor

In areas such as agriculture or construction, there has been a dramatic decline in the availability of labor. In many fields, a significant share of workers has been removed from the labor roster due to being mobilized for the reserves, which also limits their “unmobilized” spouses’ ability to work. In general, the impact to the supply of labor is heterogeneous across industries, and there are factors that may compensate for it, such as the ability in some industries to bring retired employees back to work, without significant friction.[10]

The impact on the food industry: The supply of labor in the food industry and in many links in the value chain has been significantly impaired due to the war. The supply of labor in agriculture is suffering from a serious crisis in view of the departure of foreign workers from Israel.[11] Despite the broad public willingness to volunteer for agricultural work, most volunteers do not have the skill or capacity necessary for this work At the beginning of the war, the Ministry of Agriculture estimated that there was a shortage of tens of thousands of workers in the industry, and the State tried to deal with this shortage, partly through a grant program to incentivize agricultural labor. In the time that has elapsed since then, this shortage has narrowed significantly.

The supply of labor in the logistical and operational arrays of food companies was also affected by the broad mobilization of reserves, as well as by the location of some of the operations in proximity to the confrontation areas. The impact to the supply of labor also encompassed the retail segment, although there are indications that it has been easing significantly in recent weeks.

2.2.3. Technology

The term “technology” relates to the manner in which companies convert inputs to outputs. A period in which part of the workforce is mobilized or not focused on work may have a negative impact on knowledge and organizational memory, and lead to an impairment of production efficiency beyond what is caused by the impact to availability of the inputs themselves. There may also be an impact to technology if the security situation near the site of operations forces the firm to operate outside its normal work patterns.

Similar to the discussion above regarding the availability of factors of production, an analysis of the war’s impact on production technology in a given industry must include a mapping of the geographical location of most of the means of production, as well as the suppliers of the most prominent firms in the industry. The more these means are located in areas that are close to the confrontation line, the more we can expect a high number of interruptions and an impact to the industry’s supply, which would put downward pressure on prices in that industry.[12]

The impact on the food industry: A significant impact can be expected in productivity, mainly in the agriculture industry, in view of the departure of skilled workers. Many activities in this industry require skills that have a significant impact on output. Basing operations on volunteers or on temporary manpower does not enable the industry to operate at its normal productivity levels. In other fields, such as production and marketing, less of an impact to productivity can be expected.

- Market forces and the intensity of competition

Given the demand and the cost structure, the price level is also set as a function of the intensity of competition in the industry. Therefore, the third factor we will discuss focuses on potential changes in market structure and in market forces as a result of the state of war.

The COVID-19 crisis created a “playing field” that was tilted toward large corporations, since in order to continue operating, companies had to make investments that involved economies of scale, such as meeting “purple badge” conditions or preventing morbidity and infection at production and service sites. As the pandemic ended, bottlenecks further up the supply chain also acted to temporarily intensify the market power of the large companies.[13]

The current state of war is different, and it is not necessarily expected to increase market power or concentration along the entire value chain through similar channels. The Home Front Command has permitted economic activity in most parts of the country, and the effect of emergency regulations is not expected to significantly limit the activity of small businesses relative to large ones. However, there are certain conditions under which the state of war does limit small suppliers, and creates advantages for large ones.

The self-employed, and small businesses that employ a small number of workers are absorbing a significant calamity, to the point where they have to stop functioning, even if only a small number of workers have been mobilized for reserve duty. The state of war may also require adjustments that involve economies of scale. For instance, a company with a large fleet of vehicles or other significant logistics infrastructure may make adjustments even when some of its resources are shut down. In addition, the ability to hedge risks, including currency risks, may pose a size advantage in a way that is beneficial for large companies. Beyond these factors, the emergency situation may create links through which the large companies can communicate with each other, which may lead them to coordinate their operations in a way that harms competition. In this context, we note that the level of public and regulatory attention to problems of competition may be very limited during an emergency period.

In contrast, to the extent that public attention allows it, public sentiment or government measures may work against price increases (through various “shaming” phenomena) in a way that forces companies to erode their profits (markup squeeze).[14]

The war’s effect on market power exercised in the markets is not expected to be uniform, so it is difficult to see an increase in market power in view of the war as a sweeping influential factor on price levels in the market.

The impact on the food industry: In the food industry, there are two conflicting short-term effects on the market power of large suppliers. The first is that the market power of large participants may strengthen due to temporary regulatory leniencies such as an exemption from affixing price labels or shelf-arrangement restrictions by large suppliers.[15] In general, these measures will make it difficult for consumers to compare prices and for small suppliers to attain visibility. Another contribution to large suppliers’ market share is due to the natural operational impact experienced by small suppliers that are more vulnerable to foreign trade risks, currency risks, and declines in manpower due to reserve service or proximity to the border.

In contrast, the public atmosphere has the power to temporarily weigh upon the abilities of large suppliers and retailers to raise prices significantly during the war. Even under these conditions, companies along the value chain can still raise prices by taking measures that are not clearly visible, such as restricting sales promotions or shrinking packages. Moreover, in the medium term, this consumer restraint may dissipate, while some of the factors supporting the intensification of market power (such as the operational impact suffered by small suppliers) remain in place due to the continuation of the state of war. The extent of public attention to regulatory and competitive issues may have a material impact on the realization of such scenarios.

- Summary of the effects on the food industry and initial empirical findings

This section summarizes the forces operating in the food market, and assesses their overall effect. Following that, we use high-frequency data regarding consumer expenditures on food products and regarding prices in order to test the state of the market in the first months of the war. This is the place to emphasize that this analysis is not a formal examination of the hypotheses drafted in the first part of this paper, but is rather a sampling of patterns that are consistent with the economic forces that are described.

- Summary of the war’s effects on the food industry

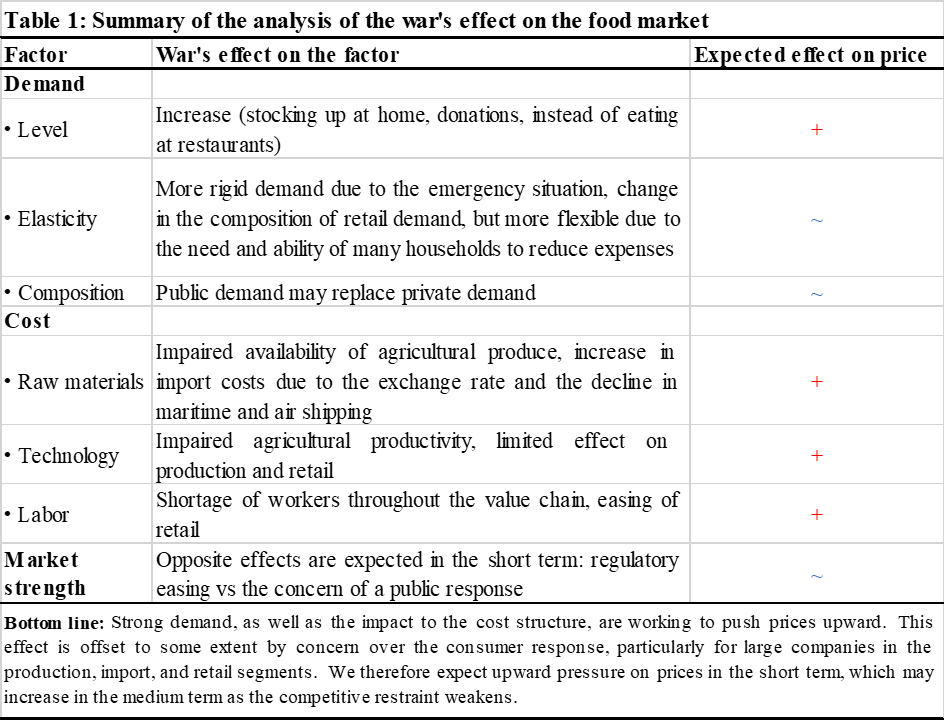

Table 1 summarizes the war’s effects on supply and demand factors in the food industry, as presented above, and provides an example of a finished product of the analytical assessment framework. The bottom line is that most of these factors work in the direction of some upward pressure on prices. In the short term, this effect is moderated by large companies’ concern over a consumer backlash or boycott of a company that significantly and openly raises prices during wartime. However, prices may actually increase as a result of less obvious measures such as reducing sales promotions or reducing package sizes. In the medium term, the competitive restraint may weaken, while in contrast, the longer the security crisis lasts, the more persistent the factors pushing for price increases are expected to be, with the potential for further price increases in the future.

- The food industry during wartime: Initial data and the development of a “rapid” index of food prices.

One of the challenges of an economic analysis during a crisis is the amount of time that passes until the effects of the crisis are clearly and fully reflected in the ordinary data series. Therefore, alongside the analytical assessment, we now present an initial real-time empirical picture of the war’s impact on the food industry, as reflected in the data currently available. This analysis distills up-to-date information from two main sources: data on credit card expenditures[16], and the retail prices database that includes information on the prices of products sold at the retail supermarket and pharmacy chains on a daily frequency.[17] As we present below, we use the retail prices database to develop a “rapid” index of food prices based on available daily-frequency and high-resolution data.

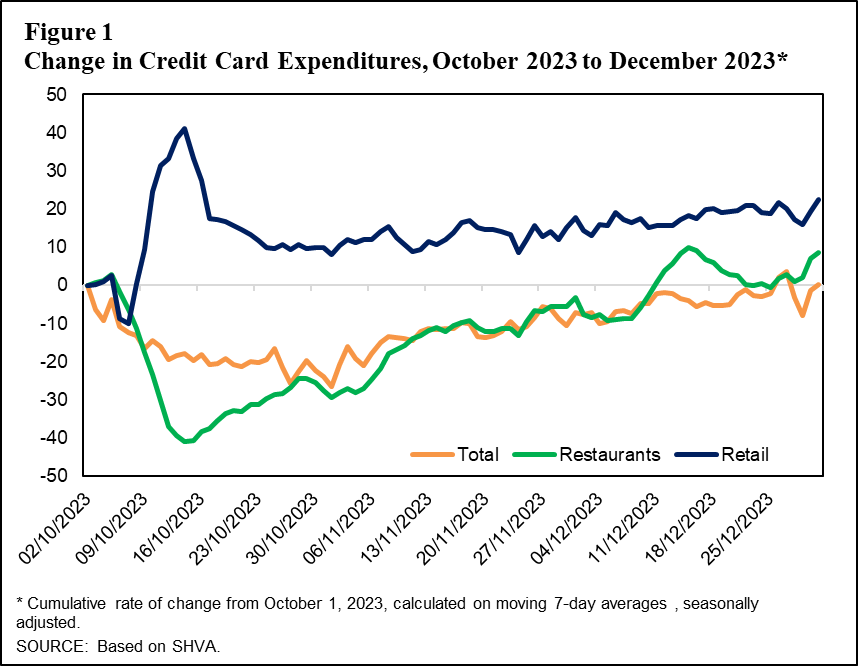

Credit card expenditures: Figure 1 shows that following the outbreak of the war, there was a jump of about 40 percent in credit card expenditures on food relative to their October 1 level. A number of days afterward, the expenditures moderated, but even after that, expenditures were still about 15 percent higher than before the war.

This increase is prominent compared to credit card expenditures excluding food, which declined by about 30 percent at the beginning, and by about 25 percent at the end of November 2023. Another interesting figure is the sharp decline in expenditure on restaurants, which is a partial alternative to expenditures on food at the supermarket chains. This expenditure declined by about 40 percent in the initial days of the war, but recovered significantly thereafter, returning to – and even surpassing – the base level.

The described dynamic of expenditures on food is consistent with the description of the war’s impact on demand, as outlined in Section 2.1 above. Demand jumped at first due to the need to stock up on food products at the beginning of the war, and then declined but remained significantly higher than its initial level, due to the other factors supporting strong demand for food during wartime. Therefore, in contrast with other industries in which a decline in the level of demand exerts downward pressure on prices and restrains the supply pressures working in the opposite direction, such a material barrier does not exist in the food industry.

The changes in credit card expenditures are a combination of quantitative changes and price changes. A priori, we cannot know whether the increase in expenditures on food is due to an increase in price, an increase in quantity, or both. In order to separate price changes and quantity changes, we must also have an up-to-date picture of the changes in retail prices themselves, as presented below.

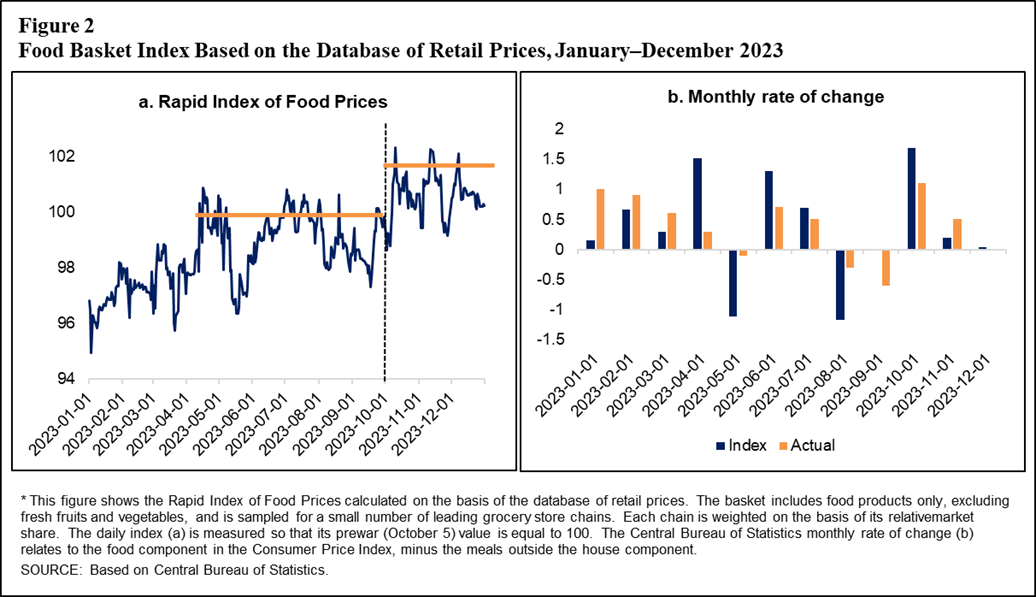

Retail prices and the Rapid Index of Food Prices. In order to provide an up-to-date picture at short time intervals regarding retail food prices, the Bank of Israel began calculating a new index that reflects the price of a basket that includes about 40 basic food products, excluding fresh fruits and vegetables (herein: “the Rapid Index of Food Prices”). It is important to emphasize that the Consumer Price Index published by the Central Bureau of Statistics is, of course, more comprehensive and precise (and is the determining index for policymakers), but the effects of crises such as a war are reflected in the CPI at a low frequency (monthly) and with some lag. Index figures for the current month are obtained only on the 15th of the following month. The Rapid Index provides an initial indication, at a daily frequency and in real time, regarding price trends.

In addition to the question of frequency, the Consumer Price Index does not reflect sharp changes in the expenditure weight of various components that take place during a crisis. The Rapid Index presented here is also based on the Central Bureau of Statistics consumption weights, and therefore suffers from a similar limitation. However, the focus on food reduces the impact of this limitation to some extent. While actual expenditure on components such as tourism and leisure decline sharply during war, we can expect that the changes in the relative weight of expenditure on various food products sold at the retail chains will be more modest.

The Index includes a list of products under four general categories: dried food, beverages and oils (rice, juice, oil, etc.); meat, poultry, and fish; baked goods; and eggs and dairy products. The product prices that appear in the Index are gathered at a daily frequency for all stores in a small number of leading supermarket chains, which constitute a significant portion of the market. In the first stage, the price of the basket is calculated for each chain in the following manner. The price of each product is defined as the median price of similar products (for example, a 1 kg package of rice) at each of the chains (covering all stores of that chain). They are then weighted in accordance with the relative weight of that product (or of a similarly defined product) in the food basket comprised by the Central Bureau of Statistics. In the second stage, the Food Index is calculated as the weighted average of the food baskets of the selected supermarket chains, where the weight of the basket in each chain reflects its relative market share.

Figure 2a shows the daily figure of the Rapid Index of Food Prices (measured such that October 5, 2023 = 100), and Figure 2b shows the monthly rate of change of the Rapid Index (monthly average compared to the average of the previous month) relative to the monthly rate of change of the Central Bureau of Statistics Food Index net of meals outside the home. Due to limitations in the data available at the time of this writing, we present the development of the Index from November 2022 to December 2023. The right side of the Figure shows that the Index reflects an increase of about 2 percent in the weighted basked immediately after the outbreak of the war (labeled with the dotted orange line), and that it remained at a slightly less high level later on, with some volatility. In total, the level of food prices increased by an average of more than 1 percent during the period after the outbreak of the war, relative to the preceding months.

The Index’s monthly rate of change that appears on the right side of Figure 2 is compared to the monthly rate of change of the Central Bureau of Statistics Index of Food Prices excluding meals eaten outside the home, in order to validate the Rapid Food Index. As we can see, the direction in previous months is similar to the direction of change in the CBS index, although it is more volatile than the CBS estimate—apparently due to the narrower focus of the basket.[18]

Conclusion: We presented both an analytical and an empirical assessment of the war’s main effects on market forces and supply in various industries. We focused on the food industry, in view of its importance and high weight in the Consumer Price Index, but the analytical framework that we presented can also be used to analyze other industries. The analytical assessment showed that the war’s overall effect on the food industry works toward putting some upward pressure on prices. This analysis is backed up by new data, which are intended to provide an up-to-date picture of conditions in the food market. The empirical analysis based on credit card expenditure data supports the conclusion that demand for food products remained strong, and even intensified, during the war, and that this phenomenon is not restricted to the initial days of the war only. The rapid daily index of food prices, which is intended to provide an initial indication of trends, is consistent with this conclusion.

[1] This analysis discusses changes in price levels as a result of the shocks to demand and supply at the industry level. It does not deal with inflation in the broad sense—a prolonged and broad macroeconomic increase in prices.

[2] The intention here is the food component in the Consumer Price Index, minus the “meals outside the home” component.

[3] The decline in the desire or ability to travel abroad also enables the diversion of demand to the domestic economy, including for food products.

[4] Changes in consumption habits make it difficult for s to interpret the inflation picture provided by the Central Bureau of Statistics, since the index is measured for a basket with fixed weights that reflect consumption habits during routine times.

[5] For instance, see the “generic drugs paradox” in the pharmaceuticals industry, where demand for brand-name drugs declines due to the entry of generic versions, but the price does not drop because consumers who continue to purchase it attribute special importance to purchasing specifically the brand-name version. Frederic M. Scherer (1993), “Pricing, Profits, and Technological Progress in the Pharmaceutical Industry”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 7(3): 97–115.

[6] In contrast, “new” consumers may show less inertia in their purchasing decisions and more readiness to try cheaper alternatives to the more expensive food brands: Alon Eizenberg and Alberta Salvo (2015), “The Rise of Fringe Competitors in the Wake of an Emerging Middle Class: An Empirical Analysis”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 7(3): 85–122.

[7] One reservation to this statement is the possibility of the war’s expansion such that it leads to a global shock with all of its consequences, including on the prices of oil and other commodities.

[8] As of this writing, the exchange rate has returned to its prewar level, but uncertainty regarding the duration and severity of the war creates a currency risk for importers and affects input purchase contracts.

[9] The five regional councils in the western Negev are responsible for about one-quarter of Israel’s field crop area, and about one-third of its vegetable crop area.

[10] See the Special Bank of Israel Research Department Analysis: “The Economic Cost of Absence from Work During the Swords of Iron War” (November 2023).

[11] In this context, it should be noted that foreign workers were among those murdered and kidnapped by Hamas, which has had an impact on moral that translates to their willingness to remain and work in Israel.

[12] The current developments may prove to be an incentive for streamlining and adopting new technologies, but they are not expected to have an impact on the price dynamics in the short term.

[13] “Further up the supply chain” relates to earlier stages, meaning suppliers and producers of the raw materials necessary to produce goods.

[14] See, for instance, “Consumer Protection (Swords of Iron – Temporary Order) Legislative Memorandum, 5784–2023.

[15] The market power of the supermarket chains may also strengthen as a result of the impact on consumers’ ability to compare prices.

[16] For an explanation of credit card expenditure data, see “Special Research Department Analysis: Credit Card Expenditures as an Indicator of Economic Activity During the Swords of Iron War”.

[17] In 2014, the Knesset passed the “Promoting Competition in the Food Industry Law”, which requires the large retail chains to report on the prices of all products that they sell in their branches each day. The Bank of Israel established and maintains a database that keeps the regular data published by the chains.

[18] Despite the relatively high variance of the Rapid Index of Food Prices, its cumulative change between December 2022 and November 2023 is about 4 percent, which is relatively close to the cumulative change of the Central Bureau of Statistics Index of Food Prices excluding meals eaten outside the home, which is 3.1 percent.